|

| Victoria Disaster, Toronto Litho Company (from Western University). |

|

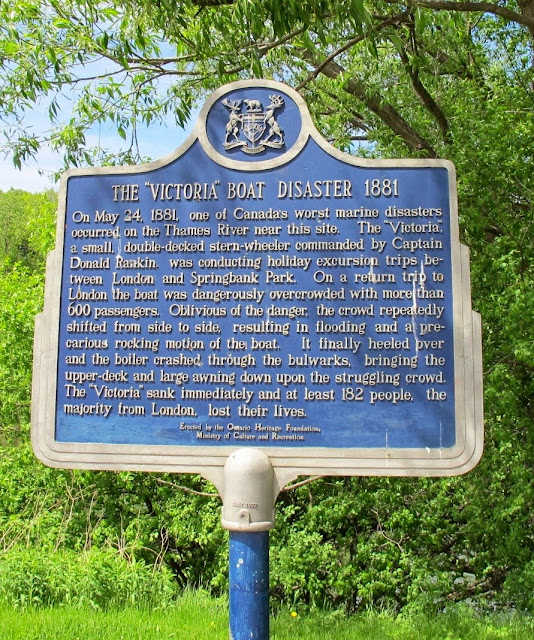

| Plaque in Greenway Park marking where it happened. |

|

| View today of where the ship sank in 1881. |

|

| Forks of the Thames today. |

River from London. However, that Victoria Day—the Queen’s Birthday—would take a horrific toll on the city of 19,000, one that would be noted in newspapers around the world.

Crowds of families with their picnic baskets gathered near the city’s Sulphur Springs Bath House at the Forks of the Thames. Three flat-bottomed steam boats were ready to take them there: the Princess Louise, the Forest City and the Victoria. A steamboat ride excited everyone. Ladies wore their Sunday-best dresses, long garments that almost touched the ground.

The crowds jostled and pushed as they paid their 15 cents for the round trip. But soon, everyone was onboard, the whistle blew and the Victoria chugged away to deliver them to Springbank Park.

Late in the afternoon when it was time to return to their homes, crowds were milling about the Springbank wharf. But there had been some difficulties with the Forest City with the result that only the Victoria showed up at the wharf.

Captain Donald Rankin couldn’t maintain order. Young men at the dock scampered over the ship’s rails, people complained. The captain tried ordering people off the ship but to no avail. The ship was soon overloaded by from 200 to 400 passengers it was later learned. The captain finally reversed the ship into the channel for the return voyage.

Only a few minutes later, the low-riding ship struck a large rock, creating a gash in the hull. Water began pouring in. Each time the passengers shifted position from one side to the other, she almost turned on her side. A bunch of unruly teens began making things worse by rushing from side to side singing, "One More River to Cross." The captain admonished them, but they simply jeered at him.

The voyage was beginning to become seriously frightening. The captain planned on running his ship aground on a sandbar just ahead. In the meantime, he refused to stop at Ward’s Hotel and later at the wharf at Woodland Cemetery—much to the chagrin of those awaiting the ship.

But a few hundred yards beyond the cemetery landing, the passengers were greeted by two racing sculls that put on a race for the ship’s passengers. As they swiftly swept by, the crowd rushed to the starboard (right) side to watch. The ship almost turned over. Terror-stricken, the passengers, in an attempt to straighten the vessel, rushed to the port or left side. Aided by the sloshing water from the gash in the hull, it was too much. The ship rolled over on her left side—the side facing away from the closer south bank.

Next, the 60 horse power steam engine's boiler, mounted rather flimsily on the lower deck, broke away and slid across the deck amid clouds of scalding steam that seriously injured some passengers and then before dropping into the river took with it the wooden posts that supported the upper deck.

Those already struggling in the water were now trapped under canvas, netting and other debris.

People attempted to climb over those above them by pulling on their legs—all of this happening just a few metres from the shoreline.

There were acts of bravery. One grandfather holding his wife against his body and a granddaughter in each arm and an infant’s dress between his teeth, made it to shore.

The long dresses soaked with water dragged many down to their deaths

According to London historian Dan Brock, two young men were found nude, lying among the dead. He theorizes that the two had been skinny-dipping when the accident occurred and had exhausted themselves to their deaths rescuing survivors.

A newspaper report of the time said, “a woman who had escaped had her babe torn from her breast by the falling of some of the timbers from the upper deck. She was taken to shore and in a few minutes saw her child float on top of the water. With a wild shriek she threw herself into the stream and saved the child, when she was with difficulty revived a second time herself. Scores of such incidents were noticed.”

Two hundred died.

Two hundred died.

To be continued.